Adoption

Adoption in the Life of Steve Jobs

Both genes and environment help account for Jobs's success.

Posted March 30, 2015

As most readers probably know, Steve Jobs, the founder and prime mover of Apple Computer was adopted as an infant. The publication this week of a new biography about him pushed me to resurrect notes I made in 2011 at the time of Jobs' death at age 56 and my reading of his authorized biography by Walter Isaacson released about the same time. I have not read the new book, but from reviews and discussions in the press, I doubt if it will throw new light on the issues discussed here. But I encourage comments from those who read Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli. Becoming Steve Jobs.

Until he met his biological sister, the novelist Mona Simpson, when he was in his late 20s, Jobs thought that a person’s success or failure was largely the result of one’s upbringing, along with timing and luck. Certainly, his life story until then supported this view. Raised in a stable, lower middle class adoptive family, Steve grew up in a setting that was especially conducive to developing an interest in computers. His father, Paul, was a machinist, who Steve called “a genius with his hands.” Paul in his spare time rebuilt old cars, something that didn’t interest Steve. But his father taught him the rudiments of electronics and Steve loved weekend scavenger hunts with him looking for spare parts. Steve’s adoptive parents were warm, loving, and made him feel special. They carried out their promise to the birth mother to send Steve to college, where he dropped out after one year.

Jobs lived in Mountain View and then in Los Altos, California, in the heart of an area that in 1971 was named Silicon Valley. Many of their neighbors in the 1950s and 1960s were engineers. Jobs told Walter Isaacson:

"Most of the dads in the neighborhood did really neat stuff, like photovoltaics and batteries and radar. I grew up in awe of that stuff and I asked people about it."

When he was 13, one of these neighbors got him into the Hewlett-Packard Explorers Club, a group of about 15 students who met for talks from company engineers. It was there that he saw his first desktop computer. “I fell in love with it,” Steve recalled. This club gave him the leverage to call up Bill Hewlett when he needed a particular part for a school project. That phone call led to a high school summer job at Hewlett-Packard. Here he met Steve Wozniak, five years his senior, with whom he would go onto found Apple Computer in Jobs' garage, a few years later.

If Steve’s biological parents had married (as they did several years after they put him up for adoption) and had raised him, the environment would not have been as conducive to a budding computer entrepreneur. His birth parents divorced after a few years and both led nomadic lives. (Mona Simpson has written autobiographical novels about Steve’s—and her—birth mother in Anywhere But Here and about their biological father in The Lost Father.)

But other children, adopted or not, who grew up in Silicon Valley at the same time as Jobs didn’t develop an interest or ability in computers. Nature enters here. Even as a preteen, Steve, who loved his adoptive parents, realized he was smarter than them. Aspects of Steve’s character, ones of which helped make him create the greatest business executive of our era, probably have a genetic basis. Certainly, his intelligence, his intensity, his drive to work and succeed, his passion about design, his perfectionism, and his charisma were not determined by his parent’s child rearing nor by the larger environment.

When Jobs found Mona Simpson in the early 1980s, he was struck by the similarity in their intensity, traits and appearance. They became close friends, while he had little in common with the adoptive sister with whom he was raised. Yet Jobs had only limited contact with his birth mother and refused to meet his biological father, John Jandali. From recent interviews with Jandali, we know that he was born and raised in a prominent family in Syria, who owned villages and vast amounts of land. After receiving his Ph.D. in political science at the University of Wisconsin, Jandali decided against returning to Syria, taught briefly at a few universities in the U.S., and then became a businessman, owning and managing a number of retail restaurant and entertainment establishments in different parts of the U.S. At 80 years old, he is still working as the manager of a casino in Reno. Not a businessman of Steve Jobs stature, but a businessman none the less.

We don’t know why Jobs refused to meet the birth father, who wrote to him and wanted a relationship. Sometimes adult adoptees don’t want to hurt their adoptive parents, but they were already deceased when his birth father contacted him. And how can we understand some of Jobs' negative character traits—his arrogance, coldness, rudeness, a need for control, extreme mood swings, and emotional volatility? Would the contemporary commitment to open adoption, where there is the possibility of ongoing contact between the adoptee and his birth parents, have mitigated some of the personal costs Jobs suffered? Even if we don’t discover the answers to these speculations, looking at Jobs’ life raises questions about the interaction of nature and nurture, genes, and environment in adoption stories.

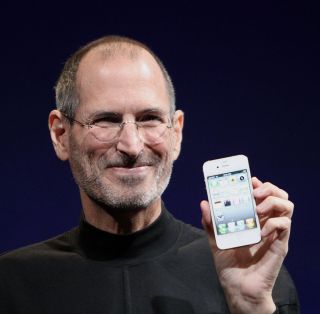

Image credit: "Steve Jobs shows off the iPhone 4 at the 2010 Worldwide Developers Conference" by Matthew Yohe used under